MY TRASH, YOUR PROBLEM – I DON’T THINK SO

Other than this prologue, and a few punctuation corrections, the following is a copy of a presentation that I was asked to make to the Sierra Club many years ago. While some of the information and the charts are dated, it still contains some good information on the history of trash that I was able to gather from the internet, and to events that had transpired, here in Granada Hills. I did not annotate/credit all of those portions of articles utilized with the source nor the author, since this presentation was intended to be given verbally, however, I have done my best to go back and add them in double brackets (( )).

My name is Wayde Hunter, I am the President of the NVC.

I am also a member of the GHNNC Board and a member of its Land Use Committee, a member of the County Alternative Technologies Subcommittee, a member of the City’s CAC – Sunshine Canyon Landfill, Vice-Chair of the County’s CAC – Sunshine Canyon Landfill, past Vice President of the Environmental Affairs Commission for the City of Los Angeles, and a past member of Mayor James Hahn’s Landfill Oversight Committee.

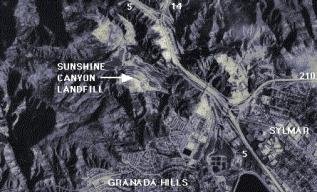

Possibly, some of you are wondering where the heck is Sunshine Canyon.

For you that already know, I really appreciate your interest and your past support on Sunshine Canyon Landfill, …and yes, it is in Granada Hills (point to map of San Fernando Valley/GHNNC). I know that you are all environmentalists seeking to preserve our flora and fauna and that this landfill has affected and destroyed a valuable ecosystem. I also know that as citizens of the City of Los Angeles you are concerned about the vast amounts of trash that we generate, what we can all do to conserve our resources, and how we can eliminate landfilling in our City and County.

I believe the Sierra Club notice stated that I would speak on the politics of trash, tell you how trash was handled in LA in the past, and to help you understand how Sunshine Canyon Landfill developed into the mega-dump that it is today, and the toxic threat it now poses to the entire city of LA. Finally, I will speak to attitudes about recycling and resource recovery, and where they are heading.

HISTORY OF TRASH

Deciding what to do with garbage is not a new problem. People have wrestled with the trash problem ever since they abandoned their nomadic ways. The Mayan Indians of Central America had dumps that exploded occasionally and burned. They also recycled, and homemakers didn’t sweep trash under their rugs. Some (trash) was trampled underfoot and some were swept into corners. When it got too deep, they would bring in the dirt to cover it ((Excerpt from Do you want to be a garbologist? by Roberta Crowell Barbalace)).

The Greek city-state of Athens opened the first municipal dump more than 2,500 years ago. Regulations required the waste to be dumped at least a mile from the city limits.

During the Middle Ages, European city dwellers threw their garbage out the door and onto the street. The people of the time didn’t understand that many diseases are caused by filthy environmental conditions.

In the late 1700s, a report in England finally linked disease to unsanitary waste disposal. The age of sanitation began. Cities began collecting waste to get it off the streets and out of public waterways. By the late 1800s, Europeans were even burning their waste and using the energy from it to produce electricity.

The situation was a little different on this side of the Atlantic. To the early colonists, America offered a seemingly endless supply of land and natural resources. So when dumping on city streets became intolerable, they simply took their waste to a dump outside of town, using the spot until it was filled before moving on to another site ((Excerpt Interesting facts, The Garbage Project, https://web.utk.edu/~jenscag/IT577/thegarbageproject/activities.htm)).

So, very quickly then, Los Angeles was founded September 4, 1781, as El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de la Porciúncula (The Village of Our Lady, the Queen of the Angels of Porziuncola.

It became a part of Mexico in 1821, following its independence from Spain. In 1848, at the end of the Mexican-American War, Los Angeles and California were purchased as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, thereby becoming part of the United States. Los Angeles was incorporated as a municipality on April 4, 1850, five months before California achieved statehood ((Excerpt ABOUT LOS ANGELES, SAN PEDRO, AND LONG BEACH, CALIFORNIA, https://www.spokeo.com/562-area-code)).

Railroads arrived when the Southern Pacific completed its line to Los Angeles in 1876. By 1900, the population had grown to more than 102,000 people, putting pressure on the city’s water supply. The 1913’s completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, under the supervision of William Mulholland, assured the continued growth of the city interestingly enough it terminates next to the present day Sunshine Canyon Landfill. The post-war years saw an even greater boom, as urban sprawl expanded the city into the San Fernando Valley.

There is not much written on the actual practices of the inhabitants of Los Angeles, but I assume that they paralleled the ideas of the day, the changes in the ethnicity of the peoples, and the subsequent developments in Europe. From the sleepy Spanish town where drinking water came in a ditch from the river and trash was consigned to empty corners or midden heaps – to the urban sprawl of today with the many small dumps that preceded the city’s expansion with trash finding its way into the hills, canyons, and old gravel pits. Dumps were even becoming a popular way of reclaiming swampland in the 1920s while getting rid of the trash.

Garbage By Any Other Name

People who study garbage use the term municipal solid waste (called MSW) to describe our trash.

Municipal solid waste is the food you didn’t eat for dinner, old shoes, the empty jar of peanut butter, or the wrapper from your candy bar.

Based on old maps, we see that these dumps progressed from downtown in a northerly direction to the San Fernando Valley following roughly along the same route as the I-5 freeway. They were usually located in gravel pits that had been abandoned because they had reached the water table or for a lack of suitable material. This use seemed at the time a good way to fill them up, recover the land, and solve a problem at the same time. These small dumps usually did not exceed more than 20,000 tons of trash during their entire lifetime (less than 2 days’ worth of permitted trash at Sunshine today).

Over time, the garbage problem was increasingly seen as a technical problem, and accordingly, fell into the hands of sanitary engineers. This meant that from the 1920s through the early 1960s, the main focus was on technical disposal methods such as incineration and, increasingly, the sanitary landfill. “Sanitary” however is an oxymoron as no landfill is “sanitary” but the word is used as a ploy to get the people to believe that all the filth and toxics buried there are now sequestered until such time as they are no longer a hazard to the public. Nothing could be further from the truth….

In the 1960s, more people became involved in garbage issues as those living near disposal sites became ardently opposed to them and it became almost impossible to site new disposal facilities. Garbage was now increasingly seen as a national crisis rather than simply a municipal problem. This shift resulted in a new focus on recycling.

THE NATURE OF GARBAGE

Garbage has changed over time. In the late 1880s and early 1900s, garbage was primarily ash from home stoves, animal droppings, and food wastes. In Los Angeles, for many years trash was separated with recyclables such as glass, metals, grease, fats, and rags being withheld with only the unrecoverable or contaminated waste being incinerated in their own back yards.

By the 1990s, the makeup of garbage had changed dramatically and was increasingly dominated by consumer products, which are very different in nature from the earlier wastes (and are associated with different hazards).

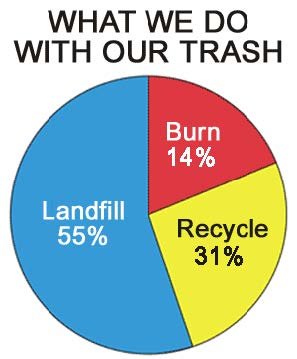

As America’s population grew and people left the farms for life in the city, the amount of waste increased. But the method of getting rid of the waste did not; we continued to dump it. Today, about 55 percent of our garbage is hauled off and buried in landfills.

What material do you think makes up most of the municipal solid waste in this country? Paper? Plastic? Metal?

If you said plastic is number one, then you agree with most Americans. But you would be wrong. The correct answer is paper. By weight, paper accounts for 35 percent of the municipal solid waste stream. Plastic accounts for 11 percent by weight.

Until 1990, government reports always tabulated the amount of waste produced in this country by one measure—weight. People use weight to measure MSW because it is the most accurate measurement available. After all, the weight of the waste taken by trucks to landfills is the same as the weight of the waste buried in the landfills.

Until 1990, government reports always tabulated the amount of waste produced in this country by one measure—weight. People use weight to measure MSW because it is the most accurate measurement available. After all, the weight of the waste taken by trucks to landfills is the same as the weight of the waste buried in the landfills.

To figure out how long a landfill will be functional, however, weight doesn’t matter. It is the volume of the trash that is important, not how much the trash weighs. As one researcher said, “Landfills don’t close because they’re overweight; they close because they have reached their volume capacity.” So, for Sunshine Canyon, since they were given 90 million tons more, with the (current) rate of compaction and based on available airspace, in reality they can get in from 125 – 140 million tons of trash.

Americans are producing more waste with each passing year. Over the past 30 years, the waste produced in this country has more than doubled, from 88 million tons in 1960 to about 236 million tons in 2003. Some of this increase is linked to U.S. population growth. After all, there are more Americans today than there were in 1960. But that doesn’t account for the whole increase.

Our lifestyle has changed, too. People are buying more convenience items and more disposables, and they choose from a wider variety of products. Today, the average American generates 4.5 pounds of trash every day. That’s 1.8 pounds more trash than the average American produced in 1960.

However, the news isn’t all bad. For the first time, the Environmental Protection Agency predicts Americans will stop increasing the amount of trash they throw away each day. For the next few years, the government predicts the average American will continue to generate 4.5 pounds of trash per day. Source reduction, like composting and reduced packaging, will play a major role in this leveling.

THINK BEFORE YOU THROW – A TRASH TIMELINE (AVERAGE NUMBER OF YEARS SOMETHING LASTS)

- Paper: 2 -4 weeks

- Banana Peel: 3-5 weeks

- Wool Cap: 1 year

- Cigarette Butt: 2-5 years

- Disposable Diaper: 10-20 years

- Hard Plastic Bowl: 20-30 years

- Rubber Sole Shoes: 50-80 years

- Tin Can: 80-100 years

- Aluminum Can: 200-400 years

- Plastic Six-Pack Rings: 450 years

- Glass Bottles: FOREVER

POLITICS OF TRASH IN LA

So let’s talk a little about some of the politics of trash.

In 1961, Sam Yorty ran successfully for mayor of Los Angeles on a platform to end the inconvenience of separating refuse. A city ordinance eliminates the sorting of recyclables.

When John Stoddard joined Mayor Bradley’s office in 1986, the City Council was in the process of authorizing the LANCER project, a plant at 41st and Alameda that would burn trash at high temperatures and convert it into electricity. Bradley’s appointees to Public Works were championing the project; the late Councilman Gil Lindsey wanted it in his district, and it seemed as if the mayor was behind it, too. (Although, at a later point, Gil reminded John that he’d hadn’t taken a position on it yet. He was canny that way.)

When John got reassigned in early 1987 from his press office to the position of Senior Advisor for environmental policy, LANCER was one of the issues he had to figure out. The mayor was coming off a landslide defeat in his second try for governor, and some of George Deukmejian’s surrogates had made hay with the city’s leaky wastewater system spilling raw sewage into Santa Monica Bay. This not only hurt Bradley’s chances to rally the Democratic troops against the incumbent, but it also created an opening for Bradley to be challenged in 1989 from the left, by a candidate who would promise a more environmental administration. That candidate looked to be then-Councilman — now-Supervisor — Zev Yaroslavsky ((Excerpt Trash Politics, by Kevin Roderick, March 22, 2006)).

John started reading EIRs. What is this environment thing? How does it work? He delved deeply into LANCER. The mainstream environmental groups were quiet about it. The Sierra Club, more influential locally then than now, was officially neutral. But one outlier group, Citizens for a Better Environment (now Communities for a Better Environment) and a then-new group, Concerned Citizens of South-Central Los Angeles, had gotten organized and were starting to raise the issue of how a trash-burning plant in South-Central would affect the health of nearby residents. They pointed out that no one was talking about building a plant like this in West LA or the Valley. Why should SouthCentral take anyone’s word that LANCER was safe if the rest of the city didn’t want it in their backyard?

The fight against LANCER was one of the first “environmental justice” campaigns. Concerned Citizens was an outstanding example of grassroots organizing.

It was so long ago, John can’t remember the precise sequence of events — the loud protests, the quiet meetings, the disastrous public hearings — but in the end, his conclusion was the Mayor should oppose LANCER and in its place call for a citywide recycling program. At that time, the only curbside recycling going on in LA was a pilot program in Pacific Palisades that seemed designed to prove only that recycling was expensive. Until Los Angeles was recycling as much as it could, he believed the public would halt every other waste disposal idea — whether it was waste-to-energy or new landfills. He also didn’t see how the city would be able to follow through on the plan of building a dozen waste-to-energy plants because of the cumulative air emissions. But building only one didn’t make sense, because its impact on trash diversion would be so minimal.

Bradley did not want to simply kill the LANCER project without announcing recycling as an alternative, so John needed to get the Bureau of Sanitation to agree that a citywide recycling program was feasible, or at least to agree not to shoot it down. At first, they resisted and tried to “educate” him out of citywide recycling. But, to give credit where it’s due, after they realized recycling was their future, they embraced it, and over the next few years established the largest municipal curbside recycling program in the nation. It was Del Biagi, the bureau’s director, who said, “Why don’t we commit to recycling 50 percent of our waste?” And that became our goal. AB 939, the state law that mandated 50 percent recycling statewide, came later, its authors clearly empowered by Los Angeles’ ambitious target.

Bradley did not want to simply kill the LANCER project without announcing recycling as an alternative, so John needed to get the Bureau of Sanitation to agree that a citywide recycling program was feasible, or at least to agree not to shoot it down. At first, they resisted and tried to “educate” him out of citywide recycling. But, to give credit where it’s due, after they realized recycling was their future, they embraced it, and over the next few years established the largest municipal curbside recycling program in the nation. It was Del Biagi, the bureau’s director, who said, “Why don’t we commit to recycling 50 percent of our waste?” And that became our goal. AB 939, the state law that mandated 50 percent recycling statewide, came later, its authors clearly empowered by Los Angeles’ ambitious target.

Things have moved quickly. Councilman Greig Smith’s RENEW LA plan sets a goal of 100 percent recycling — zero waste. But it also talks about “harnessing the energy potential of ‘waste’ by utilizing new technology to convert the material directly into green fuel, gas and/or electricity.” Of course, that was the fine idea behind LANCER.

Don’t get John wrong. That was then, and this is now. John has read over some of Councilman Smith’s plan and it is clearly about as comprehensive as one could hope for. Greig Smith got elected knowing the Sunshine Canyon landfill was his albatross, so he made himself an expert on all the recycling and reuse options out there. And he’s right on the money when he compares the costs of recycling and reuses with the anticipated future cost of the only other options — hauling the trash hundreds of miles away to distant mega-landfills via train or truck. However much waste the City can divert from that expensive, polluting parade, all to the good.

I would like to point out that although the LANCER incinerator proposed for South Central Los Angeles in 1983 was canceled in 1986 by Mayor Bradley after three years of opposition by local residents over concerns about increased pollution and garbage truck traffic, however, the City of Commerce incinerator was proposed and later built in 1986, a few miles east of South Central Los Angeles. This refuse-to-energy plant burns 4,000 tons of trash daily and produces enough electricity for 10,000 homes. The plant is operated by the Sanitation District of Los Angeles County.

Because of public opposition to siting new landfills, by the time that the 90’s arrived the politicians, and the agencies realized that the only way to continue landfilling was to increase the permitted capacities of existing landfills.

The County of Los Angeles produced a “Time to Crises” report and indicated that out of 106 sites in all of the County of Los Angeles only 6 were viable. All these were of course on the City/County line and in the San Fernando Valley area. Brown’s Canyon, Elsmere Canyon, East Canyon, Rice Canyon, Towsley Canyon and yes of course Sunshine Canyon. This was in part due to a vow to make Los Angeles deal with its trash after the County’s Mission, Rustic and Sullivan Canyons had been closed by the City.

Part of it however was to divide and conquer. Out of the 6, only Sunshine was an active landfill, so it was easier to divide the public opinion with people saying “why not Sunshine it is already destroyed” rather than establishing a new landfill in other pristine untouched canyons. Even if the County did not own the new landfill they would still benefit. The County (and the City) still stood to gain from whatever landfill was developed by the use of “tipping fees” which they can and do place on Sunshine Canyon today.

As of 2003, the country’s top three garbage firms controlled more than 40 percent of the almost $45 billion market (Waste Management Inc., Browning-Ferris Industries, and Allied Waste). Viewed from the outside, this momentum appeared to hit a snag when, in 1991, the EPA instituted tighter controls for landfills. While further regulation may have seemed like a good move for the environment and an obstacle for the garbage corporations, in reality the big players benefited. The measure, known as Subtitle D, required all landfills to protect against groundwater and air pollution by converting to “dry tomb” technology; this entailed the costly installation of liners, along with gas and liquid leachate collection and monitoring systems. The big trash firms liked Subtitle D because it created barriers to entry for their less capitalized, smaller rivals and would price out many municipalities, facilitating yet further consolidation of the waste industry.

With their competitors on the ropes, the conglomerates went on a buying spree, plucking up defunct dumps to upgrade and opening new disposal sites in regional hubs like Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, and Michigan. Here the trash corporations built mammoth new “mega-fills,” giant disposal sites fully outfitted with all the required monitoring equipment.

During this time, the overall number of landfills nationwide declined as substandard dumps were shuttered. But meanwhile, under the conglomerates, actual burial capacity soared. The additional cost of new regulations was becoming enormously expensive. The way much of our politics still work today is that the trash industries give large campaign donations to the politicians that they think will win or who are planning to run again, and they do this either directly or covertly through the consultants and law firms they retain; expecting that these politicians, in turn, will do special voting favors for them. They even maintain a cadre of lobbyists in Sacramento.

A case in point of what money can buy in relation to the polluted Santa Susana Field Lab is the following from an article by Chris Rowe in the Daily News. “According to recent news reports, big-business contributions to Schwarzenegger’s campaigns have exceeded $125 million over the past four years. And experiences tell us that big-big business dollars can have an enormous influence in the crafting of state policy.

Emily Chung, a student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, conducted a study on the relationship between Boeing’s donations to state representatives and the way those representatives voted on matters related to the Santa Susana Field Lab. Chung found that in the case of State Sen. Kuehl’s previous bills to clean up the site, there was a direct correlation between how much money Boeing had contributed to a representative and whether he or she voted no or abstained (which is effectively the same as a no vote). “

The North Valley Coalition tried for many years to fight the expansion of the Sunshine Canyon Landfill both in the County and in the City but the political contributions, and the industry’s high priced lawyers were too much for us to counter — therefore many times the politicians’ vote went against us or the mitigations and conditions that were placed on their operations were eventually watered down with words such as “may, if necessary, as needed” rather than “shall or will”.

So we decided to think outside the box and try another approach. If we could not stop the use of urban landfills or their expansion then we would try to remove, divert, or dry up the source of their business.

Let’s face it folks — landfilling is archaic.

Burying garbage is a total waste of our finite resources and a cruel legacy of pollution that we leave for the neighbors around these landfills and for our children to deal with in the future.

The NVC started by agitating the politicians and governmental agencies to push for more recycling of garbage, such as plastic bottles, cans et cetera, to use alternative technologies, and to institute tougher environmental protections. The recyclable items would be taken out at the material recovery facilities (MRFs) and would never go to a landfill. Many recyclables are currently sold to businesses in the USA and overseas while others are waiting for markets to develop. Both the City and the County are working towards establishing conversion facilities in the near future that would take the residual waste destined for landfills and use it for generating power or for producing a commodity such as oil or compost. The County is pairing new technologies with MRFs so that whatever cannot be recovered at the MRF and would have gone to the landfill will be the feedstock for a facility that will either produce electricity or another useable product such as LNG or compost with little or no pollution or residue. The City, on the other hand, will also use new technology but it will be freestanding with its secondary presorting and not require an MRF because it will use black bin material which has already had most of the recyclables separated by residents into blue and green bins.

In the case of Sunshine Canyon Landfill, the City of Los Angeles is now required by mandate, thanks to the RENEW LA program, to keep reducing the amount of garbage they deposit each day. Most recently we were able to get the County Supervisors to agree that Sunshine would not take any garbage from outside of LA County.

The NVC are stakeholders and participants in Zero Waste, SWIRP, RENEW LA.

For those of you who wonder why we still fight. Yes, we lost a closed canopy oak forest, a riparian woodland, and many acres of wetlands but we have also won by helping to save many of the remaining thousands of acres of Significant Ecological Area #20 and we have save the rest of the Santa Susana Mountains from being turned into a series garbage dumps.

As all of this was going on we were also able to help close Lopez Canyon Landfill in Pacoima, and the Bradley Landfill in Sun Valley. We were able to create along with your help the Santa Clarita Woodlands Park and to have the Santa Monica Conservancy buy out 3 of the other 6 sites pegged by the County for future landfills that I mentioned earlier. These are Rice Canyon, East Canyon, and Towsley Canyon.

HISTORY OF THE DUMP

Sunshine Canyon landfill or dump began as an illegal operation in the mid 1950s. The complaints of neighbors forced the owners who operated under the name of Bentz Disposal to make an application for a zone change and get a Conditional Use Permit (CUP) under the name of North Valley Land Development Corporation in order to legalize it. In 1958 the Zoning Administrator conditionally granted the variance on a temporary basis for a period of ten years. At that time, they were taking 400 tons/ week of “wrapped garbage”.

In September 1966, the operator applied for and was granted another variance by the City. The early application for an expanded site was due to the fact that the operators had already exceeded their permitted elevations. The operators were then issued a 25-year variance.

In 1978 BFI bought the dump out from under the City who at that time was negotiating to buy it and turn it into a Class I Landfill.

For those of you who are not aware, a Class I landfill is one that takes toxins. So, in a way, we were better off with BFI’s Class III landfill which is allowed to take on MSW (Municipal Solid Waste) but no toxins.

But better off is only subjective. BFI subsequently began taking far more trash than the amount indicated in the operating permit (300 tons per day) and violated the operating hours, exceeding their elevations and permitted boundaries, even going into Significant Ecological Area #20. In doing so, they removed an oak tree woodland without a permit, encroached into the primary watercourse with trash, and destroyed federally protected wetlands.

After a couple of years of BFI’s management, things changed drastically for the neighbors. There were clouds of blowing dust and debris that rained down upon the community of Granada Hills. The dust was so bad at times, that residents would wake up with their houses filled with dirt on an almost daily basis. Cars left outside became dusty overnight. Swimming pools would get muddy. Skylights were totally covered in dust, and gutters full of dirt. Windows couldn’t be left open.

Neighbors cleaning up yards would find windblown trash bearing such sensitive materials as financial and medical records from surrounding cities, even blueprint drawings for Rockwell’s B1B bomber. The hills of O’Melveny Park (the second largest park in LA) had trash embedded in them. Residents on every nearby street started complaining regularly about the odor and even people driving by the neighborhood started registering complaints. Granada Hills community members could no longer entertain in their yards.

In 1988 due to increasing violations of the permit and conditions of their Conditional Use Permit (CUP), and due to complaints from the residents living near the dump, a revocation hearing was held and the Zoning Administrator ruled that the operators had violated their permit by causing conditions that were “materially detrimental to the surrounding community”, by exceeding their prescribed elevations and their variance line, coming too close to the watercourse and Bradley Avenue, and operating too close to the ridgeline. In an attempt to cure (legalize) the violations BFI was given a Curative Variance (the only one ever granted by the City) encompassing the land they had illegally used. The variance expired in September 1991 and the landfill closed. At their peak, BFI had been taking 7500 tons of trash per day.

Can you imagine from 400 tons/week to 7500 tons/day?

In 1988, the Granada Hills/ Porter Ranch/ Northridge Fire started on BFI’s property where the landfill gas was burned off with a flare. The flare was well below the landfill on the southern side, dangerously close to homes, and the fire which subsequently cause $21 million in damages started just 400 feet to the southeast of the flare on a windy night with trash raining down from the dump above over its exposed flame in a scenario as predicted by the NVC one year earlier.

My gosh, you are going to say. He is going to give me the entire history of the landfill. Not exactly but I want you to listen closely to the” failure to comply with the land use conditions” and “the failure of the City or subsequently the County” to hold them accountable.. How BFI’s bad behavior was rewarded with even more expansions.

By 1989, BFI produced for the County a Draft EIR for a 215-million-ton landfill that would include both City and County which would be completed in 3 phases. Phase 1 – County, Phase 2 – back to the City, Phase 3 – County again. This would be the world’s largest landfill – a plan and a concept that they have not abandoned.

Remember this – “the world’s largest landfill.” 215 + 25 old city = 240 million tons. Larger than Freshkills, New York at 100 million tons.

In 1995 the County ended up approving a 17-million-ton County landfill which allowed 6600 tons/day of trash contingent upon BFI applying to the City for another City expansion but only after $300,000 had been made in political contributions to the Board of Supervisors. The County side opened in 1996. Six short years later its vaunted single liner system was leaking.

In 1999 the City Council approved a 90-million-ton City/County landfill by 8-7 vote allowing 5500 ton per day expansion on the City-side after $600,000 had been made in political contributions.

We know a lot more about landfills now and the alternatives. In 2000, the residents were able to get an audit of the California Integrated Waste Management Board.

Sunshine Canyon faired poorly in it and after that, the Senate Select Committees on Urban Landfills was formed and most elected officials in Los Angeles have now come to agree that landfills do not belong in urban areas. Hence the reason Mayor Hahn had promised Granada Hills that he would not renew the City of L.A.’s contract with BFI in 2006.

Of course, politics being what they are he was replaced by Antonio Villaraigosa who also promised during his election campaign not to renew the contract. We all know what happened next – he did not live up to that promise.

In 2005 the County Solid Waste Facilities Hearing Board approved the use of Construction & Demolition Waste (C&D) as Alternative Daily Cover (ADC) opening up the County side (banned by City) to material potentially contaminated with asbestos. The NVC appealed to the California Integrated Waste Management Board (CIWMB). Needless to say, the board upheld the appeal after they inspected BFI’s subsidiary (who was supplying the C&D material) and just as our attorney had claimed, this material was contaminated and did not qualify as C&D. BFI was ordered to cease taking the C&D material.

Also in 2005 the City landfill reopened.

In 2006 the Council approved a 5-year contract option with BFI, a diversion of 600 tons/day, a $2.50 per ton increase for pass-through costs, and the right to divert. The balance of 2500 tons per day is to be accomplished by Sanitation. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa in a press conference pledged to end the City’s dependence on dumps, set a recycling goal of 70% of the refuse by 2015 – five years earlier than the current goal, and to convert the City’s 535 trash trucks to LNG.

The saga continues today with BFI claiming to be out of capacity in the City after only using less than 2 million tons of the 55-million-ton capacity within the City. The reason – they want to go to a combined City/County landfill NOW and not wait for the 5-years that they were required to do by the City. They went directly to the California Integrated Waste Management Board in Sacramento (where they maintain a strong lobby) and asked for a new Solid Waste Facilities Permit. In granting them that permit the State refused to listen not only to the residents but the City and the County of Los Angeles. The result has been an inability for the City and the County to properly enforce their land use conditions. The situation continues today.

The most frustrating part is trying to get Los Angeles residents to understand what it is like for us in Granada Hills. What it is like to live with a business that has no honor. Whose agreements mean nothing but an expedient way of exercising their permits until the next time they see fit to discard them for the next round of expansion.

WHAT THREAT DOES SUNSHINE CANYON POSE TO THE CITY?

Apart from the fact that you have already lost a riparian woodland, a closed canopy oak forest, and 11 acres of wetlands (most of which was in Significant Ecological Area (SEA) #20 we have all suffered a corresponding reduction in air quality. The balance of this area amounting to some 30,000 trees will fall if their entire proposed 215-million-ton expansion is ever realized. The disruption of habitat and the wildlife gene flow across the Santa Susana Mountains for bears, mountain lions, and deer alike have already occurred, but it will be severed forever with another expansion.

But there is also a threat to our water supplies…. Yes, I said “our” water supplies.

The treatment and storage of water for 19 million people here in LA and southern California is directly downwind, and downstream from the landfill perched above in one of the most seismically active areas in all of California. So that water you are drinking today is coming from next to the dump from the reservoir which serves as a surge area when everybody turns on their faucets in the morning. Dust from the landfill can and does blow into the post-treated water in the uncovered reservoir, and did I mention the seagulls that feast on the trash and then fly to the nearest water (the reservoir) to drink and poop in the water. That’s right, it is post-treated water and so whatever gets in it stays in it and there is no further treatment.

If ever there was a large earthquake coupled with a 100- or 500-year flood event, potentially the landfill on the City side which was not constructed properly, could collapse and course down into the California Aqueduct penstock areas contaminating our drinking water. Or leachate could find its way through broken inlet pipes or be forced up in sand boils during the earthquake and into the unlined reservoir where post-treated water is stored. Hydrostatic pressure (the weight of water above) would not keep it out. There is no way to remove leachate from drinking water. One drop of oil will make acre-foot of water undrinkable.

Imagine a city devastated by a large quake and having no water.

This scenario is real, and it happened to us in the 1994 Northridge Earthquake but fortunately, there was no rainstorm. Granada Hills was without water for 1 week, the landfill was damaged but didn’t fail but the aqueduct pipes broke and the sand boils in the reservoir happened.

We are tired. We have taken LA’s trash for over 50 years. We have suffered greatly, and I have not even gone into the health effects such as asthma, and cancer that we experience downwind of the landfill.

So what can you do to help us. Never give up the fight to preserve open space and the flora and fauna of the greater Los Angeles area. If we cannot beat the waste giants and their political support here or in Sacramento to shut down urban landfills, then support the recycling efforts and programs such as SWIRP, ZERO WASTE, RENEW LA, and support the new technologies which will convert trash to energy or some other useful product and we will take away their business. They are not a philanthropic organization. The day they lose a dollar they will be gone.

You can start today just by separating your trash into the blue and green bins, and by remembering your friends in Granada Hills.

ALONG WITH SOME INFORMATION THAT WAS SUPPLIED COURTESY OF THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES ON ITS ZERO WASTE PROGRAM AND A SCHEDULE OF MEETINGS FOR THE REST OF THE YEAR, THERE IS ALSO AN ARTICLE THAT I WROTE SOME TIME AGO ON THE “TRASH CRISES – ANOTHER URBAN MYTH” THAT YOU MIGHT BE INTERESTED IN.

THANK YOU FOR THE OPPORTUNITY TO ADDRESS HERE TONIGHT.

Written for Los Angeles Neighborhood Council Issues (LANCISSUES) by Wayde Hunter

Trash Crisis – Another Urban Myth

There is simply no shortage of places to put LA’s trash. In fact, many local and outof-state companies are even now fighting for it and expending great sums on legions of lobbyists and swelling the campaign funds of politicians. All of this to get our garbage.

Why would anyone want LA’s garbage, you might rightfully ask? The answer is that historically premiere motivator–money. Once more the smoke and mirror experts are again applying their craft, this time it’s to statistics. Now the waste giants, BFI (Allied Waste) and Waste Management are trying to show that the only way to save the City money is to keep on dumping at Sunshine Canyon and Bradley landfills.

They have submitted unreliable and inaccurate numbers. But, as the Chief Analysts for the City, Ron Deaton who can put a spin on anything said: “It’s not as necessary to be right as it is to be definite.”

In the case of Sunshine Canyon, we were naively optimistic, believing that no one in their right mind would put a mega-dump directly adjacent to the largest water treatment and storage facility in the nation, or allow the destruction of an oak forest containing over 4000 “protected” oak trees. Unfortunately, we failed to recognize the power of money to corrupt a city and to corrupt it absolutely. The phrase “trash crisis” was invented by the industry to persuade us to believe that we would be sitting amid decaying crud if their urban dump projects were not approved. Money flowed and approvals were issued. As for Bradley, the Los Angeles County Integrated Waste Management Task Force has weighed in and said that: “Bradley Landfill and the city of Los Angeles didn’t follow proper steps six years ago when the dump was given permission to raise its height 10 feet and slightly increase capacity.”

The sadder but wiser now, we invite you to see how we came to the revelation that there was no crisis and that alternatives abound. Shortly after Jim Hahn came into office, he appointed a Landfill Oversight Committee (LOC) to provide him with recommendations toward establishing a trash policy for LA. The mayor appointed a number of persons living near these landfills as part of that committee, to represent the people most impacted by them. We won’t go into the unfortunate plight of those who live near these creeping, cancerous monsters on the land, since such a description would take up an entire supplement to this paper. Suffice to say, we were more than eager to find alternatives which we at first assumed would be hard to find.

Surprisingly, we found these alternative technologies appeared to be abundant. Each week brought calls and visits from salesmen bearing videotapes and glossy folders, produced by companies who were anxious to take City trash and turn it into all sorts of useable products. They were even willing to build the necessary facilities at no cost to the City in return for: City support, a place to locate the facility, and a guaranteed waste stream. We asked hard questions about the environmental impacts, and many of these companies were more than willing to guarantee closed systems; systems that would not vent into the air the gases which are now constantly escaping into the air and/or are being incinerated at our landfills.

We were also astounded by the hundreds of recycling facilities that are already operational in the City, and who would be happy to expand operations and to increase the diversity of the products they recycle. Some estimated that they could recycle more than 90% of the trash. We visited recycling plants and found some to be smelly and some to be clean. We slapped on sun-screen and visited remote sites, in desert locations to assure ourselves that they were far from people. Why, we wondered, didn’t LA take advantage of these offers? Again the answer was money. Private haulers head for the cheapest dumps, not the recycleries where saving resources is a priority, and sorting makes it more expensive. Nothing will change this until fees are imposed on unrecycled trash, and the price of disposal by recycling leveled.

The LOC took their mandate seriously. Among the plans that the committee ultimately emerged with was to build in each of the six designated wasteshed areas of the city, a materials-recovery facility (MRF) and a transfer-station that would recycle all materials before rail-hauling any residual waste to remote locations far from people. The Mayor accepted the plan and the committee’s recommendation to close landfills in the City when its contracts expired in 2006. Now, some of the politicians are waffling. They opine that if everyone else is still going to send their trash to Sunshine, why shouldn’t we since it’s so cheap. Their reasoning that doing the wrong thing is OK, because everyone else is going to do it, doesn’t hold up with any responsible parent, and shouldn’t reflect the ethics of our City.

Through recycling, rather than dumping, we will be able to save irreplaceable resources. This would ultimately save the costs of the cleanup of these landfills, whose incineration of gases compromises air quality, whose location poses a significant threat to the water supply, and which will continue to pollute decades after closure.

We want the City to stand firm in its resolve to build only transfer stations that have the capability of recycling all the trash before it is transferred. The City must locate these equitably throughout the city so that no one area bears more than its share. The City should seek price-leveling by putting their current franchise fees only on unrecycled trash. And, oh yes, we want the 55% of L.A. that doesn’t recycle (apartments and commercial) be included in the citywide recycling program as soon as possible. When we lose, we lose forever our precious natural resources, and we throw away not only trash but also our children’s heritage.

Wayde Hunter

Granada Hills

- President North Valley Coalition

- Environmental Affairs Commissioner City of Los Angeles

- Member Mayor James Hahn’s Landfill Oversight Committee